Originally by Khachatur Mousheghian, Revised by Aram Manasaryan

In order to gain a deeper understanding of historical issues, it is possible to gather valuable information from ancient and medieval coins and hoards of monetary issues. This method can provide insight into various aspects of a country’s or kingdom’s economy, politics, religion, art, and trade, among other areas. Numismatics, which is the study of coins, has a long and rich history, beginning with a mere interest in coins during the Renaissance and evolving into a scientific field that has proven useful for historians. The images, inscriptions, and themes found on ancient coins made of gold, silver, and copper can provide a wealth of information that is often missing from written sources. The study of coins has become an essential tool for understanding the past, as it can help shape the true history of any country.

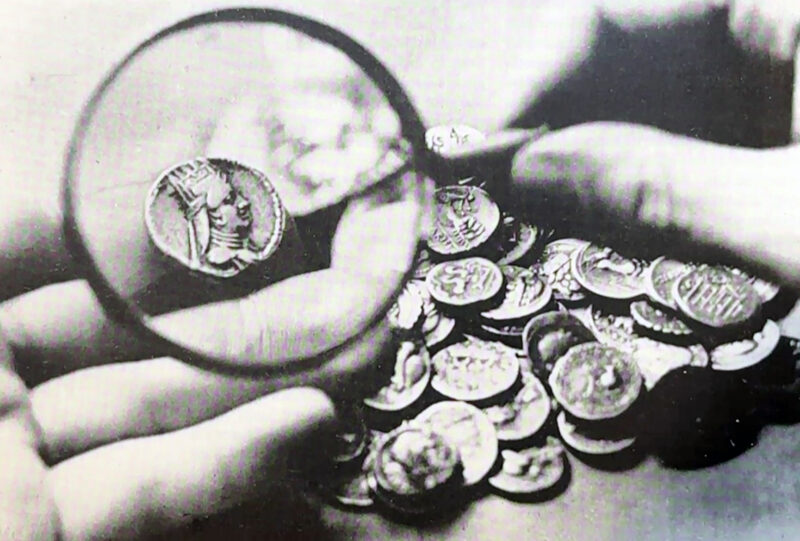

Classification of Rupenian Coins by Sibilian. Vienna 1892

Münzen & Medaillen Auction 47 Lot 824

The investigation of numismatic references to Armenia, specifically coins of Armenian origin, initially began in Europe. The Mekhitarists of Vienna and Venice significantly contributed to this field by studying and publishing valuable books about the numismatic material kept in European museums. However, to comprehensively understand the history of Armenia, it is crucial to examine Armenian coins that were used in trade relations and entered the monetary system of Armenia. Consequently, studying Armenian issues and hoards is of paramount importance.

The use of money in Armenia can be traced back to the 5th century BC, as evidenced by the early historical monuments that remain. A silver Achaemenian coin was discovered in Yerevan, two silver coins of Miletus coinage (5th century BC) found during archaeological excavations of Erebuni fortress (Yerevan), and three silver Athens tetradrachms of old style (5th century BC) found in Sisian (Armenia).

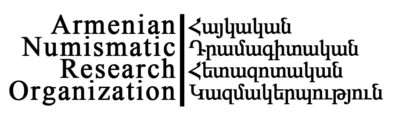

During the Achaemenid satrap’s rule of Armenia by Tiribazus and Orontes in the 4th century BC, coins were minted in towns across Asia Minor that featured their images. Specifically, in Cilicia at Issus, Mallus, and Tarsus as well as in Mysia and Ionia at Lampsacus, Cistene, and Clasomena. Although there is no evidence of the circulation of Tiribazus’ coins in the Armenian markets of Sophene and Armenia Minor, which were under immediate rule, there is no evidence to disclaim the possibility of the circulation of such coins in the western parts of Armenia.

Mallos. Tiribazos. Satrap of Lydia

388-380 BC

AR Stater

(CNG Triton XVIII Lot 689)

According to metrological data, Tiribazus’ coins served as the defining units of the Achaemenian monetary system at the start of the 4th century BC. Specifically, his double silver drachms weighed between 10.65 and 9.80 grams. Copper coins made up one-sixth of Achaemenian drachms, weighing between 0.85 and 0.51 grams. It is important to note that Achaemenian satraps of Armenia’s coins are generally rare. During this early period in Armenia, the exchange of commodities was more typical than the use of coins. As a result, it is unsurprising that pre-Hellenistic category coins were not widespread in Armenia. From late 4th century BC onwards, the Attic monetary system gradually penetrated, distributed, and established itself in Armenia. The primary units in circulation were high-quality silver drachms weighing 4.36 grams. Throughout the western provinces of the Grecian world to the northern parts of India, international trade was conducted using the Attic monetary and weight systems, which were widely accepted. The economics of Armenia, which connected with Persia, Mesopotamia, and Asia Minor, entered its Hellenistic stage of development. The old monetary and weight systems were confined to the domestic market. Most acknowledged units were: talent – 26.20kg (in Armenian – տաղանդ), mina – 436.60g (մնաս), drachm – 4.366g (դրամ), obol – 0.728g (օբօղոս), and chalci – 0.091g (քաղկոս). The correlation between these units is as follows:

- 1 talent = 60 mina

- 1 mina = 100 drachms

- 1 drachm = 6 obols

- 1 obol = 8 chalci

The silver drachm, known in Armenian sources as դրամ (dram) or դրաքմե (drachme), was the main monetary unit. Findings show that in Armenia and neighboring countries, attic drachms and tetradrachms were in circulation. The Attic gold coin, stater (weighing 8.60g), in Armenian sources is recorded as սատեր, which, however, did not play a significant role; payment was mainly in silver. The correlation between the values of gold and silver was 1:10, which could change depending on the change in the metal value. For instance, one gold stater stood for twenty silver drachms or five tetradrachms in Attic weight. The correlation between the values of silver and copper was 1:40 or 1:30, which was again not constant.

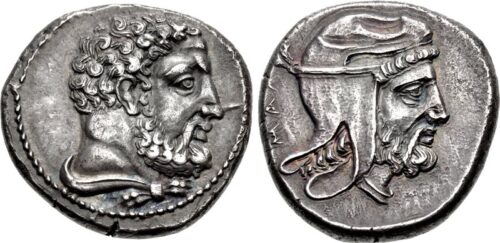

In Armenia, Hellenistic coins of local and foreign coinage were in circulation and appeared in the Armenian markets due to international trade. Local coinages were issues of the Armenian kings of Sophene and, at the end of the era, coins of the Artaxiad dynasty. All the coins found in Armenia are drachms and tetradrachms of Alexander the Great, which represent the beginning of money circulation in the country in the Hellenistic era. Silver coins of Alexander the Great in the territory of Armenia were found both during archaeological excavations and by chance during field and construction works of the local population.

Alexander III the Great

336-323 BC

AR Tetradrachm Babylon mint

CNG 108 Lot 77

The fact that silver coins of Alexander the Great were minted in Armenia’s economic centers in Mesopotamia and Asia Minor (Babylon, Miletus, Ephesus, Cardia, Abydus) suggests that Armenia had trade relations with these regions. During the Hellenistic era, drachms and tetradrachms of Alexander the Great were the most widely used coins in Armenia and its neighboring provinces in Transcaucasia, both for domestic and foreign trade. These coins were also found in hoards dating back to the 4th century BC and were issued in later periods.

In Transcaucasia, gold and silver coins of Alexander the Great were widespread. The gold coins, known as staters, are frequently discovered in the northwestern regions of the Caucasus and western Georgia, whereas silver coins, including drachms and tetradrachms, are commonly found in Armenia and the areas situated between the Araxes and Kura rivers. The circulation of gold coins in the northwestern Caucasus over an extended period led to the local production of staters inspired by Alexander the Great as early as the 1st century AD and later. However, this occurrence is not typical in Armenia. In the Armenian highlands, gold coins from Alexander the Great and his successors are relatively scarce.

Philip III Arrhidaios

323-317 BC

AR Tetradrachm Babylon mint.

CNG 106 Lot 199

In Armenia, silver coins of Philip III of Macedon struck in Babylon, Magnesia, and Colophon were in circulation, reflecting the trade relation of Armenia with the centers of Mesopotamia and Asia Minor.

During the 3rd century BC, significant changes occurred in the monetary system of Armenia. As a result of the emergence of the Armenian kingdoms of Sophene and Armenia Minor in the western regions of the country, local coinage began to be used as a means of exchange.

The presence of Sophene coins indicates the political autonomy of the region’s rulers. Although these coins were not made of silver or gold and were not used for international trade, they were made of copper and intended for use in local transactions.

Sophene. Arsames

c. 255-225 BC

AE 2 Chalkoi

Leu Numismatik Auction 15 Lot 125

The emergence of Sophene’s issues was contingent upon the progression of economics and the intensification of monetary-commodity relations within the domestic market. Although only a limited number of these coins have survived, they serve as evidence that during the 3rd century BC, the common people of Sophene utilized coppers featuring the likenesses of kings such as Arsames and Xerxes in their everyday transactions. The geographical distribution of these coin hoards highlights their regional importance. It is possible that these coins were minted in Arsamosata, which was the primary political and economic hub of Sophene.

Prior to the emergence of the Artaxiad kingdom, coins from the Hellenistic period of Armenian kings initially appeared in the regions of Sophene and Commagene, where the conditions were favorable for the development of coinage. However, these Armenian coins, which featured images of local kings and Greek inscriptions of their names, were made of copper, which limited their usefulness in foreign trade, where silver coins were more commonly used and exchanged. This difference in coinage had a significant impact on global markets. Furthermore, it is important to note that these coins were not extensively known before the end of the last century, and many of them are kept in Paris in the department of numismatics of the national library of France. However, recently new information has emerged that has expanded the scope of our presentation on the typological characteristics of the Armenian coins of Sophene and Commagene. We are grateful to Professor-Armenologist P.Z. Bedoukian for providing the numerical data. Therefore, today, this is the following copper chronology of their succession.

At the conclusion of the 3rd century BC era, a significant number of Seleucid coins, specifically drachms and tetradrachms adhering to Attic standards, were discovered in Armenian cities. These coins bore the portraits of various rulers, including Antiochus IV Epiphanes, Antiochus V Eupator, Demetrius I Soter, Alexander I Balas, Antiochus VII Euergetes, and Philip I Philadelphus, reflecting the close relationship between Armenia and Syria. Additionally, Phoenician coins, such as tetradrachms from the mints of Aradus, Sidon, and Tyre, were also found in Armenia.

In the 2nd century BC, an increase in circulation was observed. Additionally, local kings struck their own coins due to foreign trade, resulting in the receipt of foreign coinage. The political power of the Artaxiad dynasty extended over almost the entire territory of the Armenian Highland. Artaxias I united the Armenian provinces into a monarchy, which played a significant role in the international life of the Near East during the Hellenistic era.

The classification of Artaxiad coins shows that for more than a century, the Armenian kings used coins bearing their images, which are represented in the following sequence:

- Artaxias I, ca. 190–ca. 160 BC

- Artavasdes I, ca. 160–121 BC

- Tigranes I, 121–96 BC

- Tigranes II, the Great, 96–56 BC

- Tigranes the Younger, 77/6–66 BC

- Artavasdes II, 56–34 BC

- Artaxias II. First Reign, 34 BC

- Artaxias II. Second reign, 30–20 BC

- Tigranes III, 20–8 BC

- Tigranes IV. First reign ca. 8–5 BC

- Artavasdes III, ca. 5 BC–ca. 2 BC

- Tigranes IV. Second reign, with Erato, ca. 2 BC–ca. AD 1

- Artavasdes IV, ca. AD 3–ca. 6

- Tigranes V, the Cappadocian, before AD 6–12 or later

- Erato. Second reign (alone), ca. AD 13–ca. 15

- Artaxias III, AD 18–35

- Tiridates I. First reign, with Cleopatra, AD 52/3–60

- Tigranes VI. First reign before AD 60–62 or later

- Tiridates I. Second reign, and Cleopatra, AD 66–ca. 77

- Tigranes VI. Second reign, AD 66/7

As in many Eastern countries, coins in Armenia were struck by the Attic monetary and weight systems.

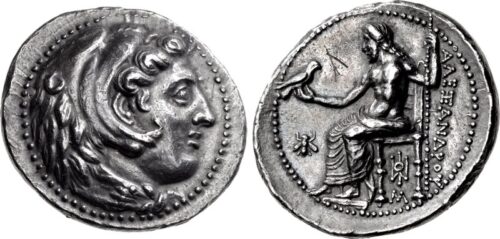

The circulation of Tigranes I’s coins was limited to the southwestern regions of the Armenian Highland. They were discovered in these areas during the reign of Tigranes II, who also saw the widespread use of Armenian coins in international trade. These coins were minted in the main cities of Armenia, including Tigranocerta and Artaxata, as well as in Syrian cities such as Antioch and Damascus. Tigranes II’s copper coins were primarily used for local transactions and are rarely found outside of Armenia and Syria. It is important to note that no gold coins were struck by Tigranes II or any of the other kings from the Artaxiad dynasty. However, gold coins from the Hellenistic-era Armenian kings have not yet been discovered. In Armenia, Syrian tetradrachms from the reign of Tigranes II were commonly used, reflecting the economic ties between Armenian and Syrian cities.

Tigranes II The Great

96-56 BC

AR Tetradrachm

Leu Numismatik Auction 15 Lot 127

After the downfall of Tigranes II, who held the ancient eastern title of “King of Kings,” the production of Armenian coins came to an unexpected halt. Under the rule of his successor, Artavasdes II, Armenian coins were only minted in Armenia. Typically, very few coins issued by the last rulers of the Artaxiad dynasty have survived to this day.

Cappadocia. Ariarathes IV Eusebes

c. 163-130 BC

AR Drachm

CNG eAuction 553 Lot 117

In Armenia, the silver coins of the Cappadocian kings were also in circulation. Hoards of drachms featuring the portraits of Cappadocian kings Ariarathes IV Eusebes (220-163 BC), Ariarathes V Philopator (163-130 BC), and Ariobarzanes I Philoromaios (95-62 BC) have been discovered. These coins were of high quality and made of silver, with an average weight of 3.82 grams for the drachms.

Parthia. Phraates IV

38/7-2 BC

AR Tetradrachm, Seleukia on Tigris

Roma Numismatics eSale 118 Lot 870

The circulation of Parthian coins from Persia and Mesopotamia had a significant impact on the money supply in Armenia. These coins were primarily issued by Parthian kings Mithridates II (123-88 BC), Phraates II (70-57 BC), Orodes II (57-38 BC), and Phraates IV (38-2 BC). Only a few rare Parthian coins have been found in Armenia, all of which were drachms and weighed around 3.4 grams on average.

In addition to coins from the Seleucid, Armenian, Cappadocian, and Parthian empires, which used the Attic weight system, early Republican-era Roman coins were also widely circulated in Armenia. During the first century BCE, the use of Roman coins in Armenia became more prevalent. At this time, the denarius, a silver coin, was a leading currency in international trade. The average weight of Roman coins found in Armenia from the second to first centuries BCE was around 3.86 to 4.00 grams of silver per unit. The average weight of post-Hellenistic drachms was approximately 4 grams. As a result, the two primary monetary units of the ancient period, the Attic and the Roman, were nearly equal in terms of their weight standards.

Asia Minor. Mark Antony and Octavia

39 BC

AR Cistophorus

CNG Auction 126 Lot 464

In Armenia, Roman silver coins dating back 80-30 years before the start of the Christian era are frequently discovered. These coins were minted in Rome and circulated alongside other issues from Gallia, Italy, Sicily, Africa, Greece, and the economic centers of Asia Minor and the southeastern Mediterranean region. Additionally, due to the international trade of silver coins from Pergamum and Ephesus, so-called “cistophorus” were also used in Armenia. These were tetradrachms of reduced weight, struck between 11.5-12.75 grams in the mints of minor Asian cities under Roman control in the 2nd-1st centuries BC. In circulation, one “kistopheri” was equal to three Roman denarii. The presence of these silver coins, along with Roman coins from Asia Minor cities, demonstrates the connections that Armenia had with Asia Minor markets during the Hellenistic era.

The coins of the Artaxiad dynasty in Armenia have unique characteristics that reflect local traditions. For instance, the coins of Tigranes I (123-96 BC) featured Greek legends that read “the Great King Tigranes Hellenophil,” indicating his Hellenistic inclinations. Tigranes II, also known as Tigranes the Great (95-55 BC), issued coins that were categorized into nine main types with variations. The coins minted in Tigranocerta and Artaxata displayed the Greek legend “King of Kings” on the obverse. The reverse of these coins depicted images such as Nike, Tyche, the mythological hero Vahagn (Heracles), a lion’s head, cornucopia, and other mythological symbols. The dating of these coins was based on the Seleucid chronology.

During the rule of Artavasdes II (55-34 BC), the title “King of Kings” that was previously accepted by his predecessor Tigranes the Great continued to be used. However, it now included the word “divine” or QEIOY, signifying a higher level of reverence. Artavasdes II’s coins did not follow the Seleucid chronology but instead marked the years of his own reign. The reverse side of his silver coins featured a quadriga or chariot with a human figure in the center, symbolizing the worship of the Armenian sun-god Areg. On the other hand, the reverse of his copper coins depicted a winged figure of Nike. During the rule of Tigranes III (20-8 BC), the king’s name was inscribed in Greek on the obverse of the coins, while the reverse read “the Great King Tigranes God.” It’s worth noting that during Tigranes III’s reign, coins were minted for the first time with a full-height image of the king holding an orb. Additionally, the Greek exergue on the coins indicated that King Tigranes was not only a great king but also a king who was devoted to his father and the Greeks.

Tigranes IV with Erato

c. 2 BC – 1 AD

AE 4 Chalkoi

BnF 41760557

Rare coins featuring the portraits of Armenian King Tigranes IV and Queen Erato, who reigned during the second year BC and the first year AD, are highly valued in numismatics. These coins were minted during a time when the local dynasty’s political power depended entirely on the Roman Empire, whose troops were stationed in Armenia. Roman authorities installed Tigranes and his sister Erato on the throne. The queen’s image, along with the inscription “Erato Sister of King Tigranes,” can be found on these coins in Greek legend. This marked the first time that a queen’s portrait appeared on Armenian coins. The use of mythological characters such as Nike, Athena, Heracles, and animals like horses, lions, elephants, and eagles on Armenian coins is a pagan characteristic that was prevalent among the Armenian people at the end of the first century BC.

Significant political changes in the late Hellenistic period, such as the decline of the Seleucid Empire in the East and the transformation of the Roman Republic into an Empire in the West, with a considerable delay, had an impact on the circulation of money in Armenia. The discovered hoards reveal that when there were no Hellenistic monarchs, their coins continued to circulate. The Mtzbin hoard, discovered near the ruins of the town of Nisibis in the southwest of the Armenian Highland, vividly illustrates the peculiarity of money circulation during this period. The extreme dates of the coins in this hoard, ranging from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD, suggest that Armenian coins issued in the 1st century BC were in circulation alongside Roman Empire coins from the 1st-2nd centuries AD. Thus, the coins of the Artaxiad dynasty remained in circulation even after the dynasty’s reign. This is not merely a chance but a natural characteristic of money circulation. As a rule, former coinage was used along with the new coins, which at first were not numerous but gradually lasted the old issues.

The Roman Empire issued gold, silver, and copper coins in order to maintain trade in Europe and Asia. The gold coins, known as aureus, had a standard weight of 8.19 grams and were widely used despite the Empire striking a large number of them. However, the silver coin, denarius, which weighed 3.90 grams and was made of high-standard silver, was also accepted as an international monetary unit. The gold-to-silver ratio was 1:12, but it was not stable. While the aureus was not commonly found in Armenian towns, the denarii featuring the image of Augustus and his two sons Gaius and Lucius were commonly circulated in both Armenia and neighboring Eastern countries.

Since denarii were widely circulated in Armenia, it is logical to assume that they were also minted in Armenia, where the Roman occupation coins of the Armenian kings were produced. It is important to note that earlier coins struck in Syria and Mesopotamia with the silver piece of Augustus had reached Armenia.

The Augustus silver coins featuring Gaius and Lucius were well-regarded in international trade and held a prominent position in facilitating transactions involving poverty-stricken individuals for an extended period. Subsequently, in various regions, counterfeit versions of these coins surfaced; however, they were not discovered in Armenia. In a similar vein, the copper coins issued by Augustus also posed challenges in terms of determining their circulation.

During the specified period, a limited number of Parthian coins were exchanged in Armenian markets. Specifically, these were drachms featuring the image of Vonones, who was a king of Armenia from 12-16 AD and, with the support of the Roman Empire, battled Parthian ruler Artabanus III. These coins were most likely produced in the mints of Tigranocerta, a location where trade routes between Mesopotamia and the markets of Asia Minor and Parthia intersected. Nevertheless, Vonones’ coins are rarely found in Armenia or its surrounding areas.

During the period between the fall of the Artaxiad dynasty and the start of the Arsacid dynasty, which lasted approximately 60 years, both old and new coins were in circulation, serving both domestic and foreign trade relations. Three distinct groups of coins were in circulation during this time:

- The coins of the first group were issued by Hellenistic monarchs from the Near East in accordance with Attic weight standards. These coins included those from Parthian and Armenian coinage, as well as the final Seleucid kings.

- The second group comprised Roman coins that were issued at the end of the Republic period.

- The Arsacid period’s principal form of currency was coins from both groups. However, during the later 1st century AD, Hellenistic and Republican coins became scarce and were replaced by coins from the third group. The Roman Empire mainly issued silver coins during this time, which were introduced by the first emperors. The majority of these coins were Augustan denarii made of high-quality silver and weighing approximately 4 grams. It is worth noting that the kings of the Arsacid Dynasty did not mint their own coins.

The Armenian kings who belonged to the central Parthian branch of the Arsacid family had the backing and support of the kings of the Arsacid family. Only the kings of the central branch of the Arsacid family had the privilege of minting coins. In the 1st-2nd centuries AD, Armenia was caught between two great powers—the Parthian and Roman empires. During this time, coins from the Roman Empire were still circulating in Armenia. Along with the coins issued by Augustus, the Vespasian and Domitian silver issues of Trajan, Antoninus Pius, and Lucius Verus were also in circulation. It should be noted that in the second century, only Roman coins were used in Armenia, and no Parthian coins were in circulation. The hoard discovered in the Garni Fortress is an important relic that reveals Armenia’s monetary circulation. It includes silver coins that were issued in Rome during the reigns of Vespasian, Titus, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, and Commodus. The latest coin in this hoard dates back to the end of the 2nd century and the reign of Commodus (182-192). The Roman coins from the Garni hoard are not only significant in Armenia but also in Transcaucasia during the 2nd century.

Artaxata. Civic Issue

55/4 BC

AE 4 Chalkoi

CNG eAuction 411 Lot 187

In addition to Roman coins, a small number of coins from the Bosporus Kingdom have also been found in Armenia. Towards the end of the 2nd century, local coins began to be minted in Armenia. The capital city of Armenia, Artaxata, issued coppers for trade in city markets. These coins were not produced by the Roman authorities or the Armenian kings of the Arsacid dynasty and instead bore the name of the city, which was then a major center for caravan trade attracting merchants from Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Persia, and the Caucasus. The coins of the city of Artaxata date back to 181-183 AD, making it the first Armenian city to have its name on coins. The appearance of these city coins is significant not only for the development of the local market but also for the political history of the region. During the time of the Roman Empire, many trade centers in the East, such as Antioch on the Orontes, Apamea, Laodicea, Nicopolis, and Damascus, had the right to self-governance. The typological analysis of Artaxata coins suggests that the Hellenistic tradition of coins was well maintained in Armenia. Mythological images such as Nike, the head of Tyche wearing a turreted crown, and Greek legends (ΑΡΤΑΞΙΣΑΤΩΝ ΜΗΤΡΟΠΟΛΕΥΣ) are characteristic elements of coins from the Hellenistic era. However, the extreme rarity of such coins prevents us from speculating on their role in circulation. Since they were made of copper, they could not be used outside of home markets. Therefore, it is expected that archaeological excavations of the ruins of Artaxata will provide new information about the local coins.

Roman coins were minted in commemoration of significant military and political events that impacted the interests of both Armenia and Rome. Even before the fall of the Republic, generals and emperors alike issued coins made of gold, silver, and copper featuring memorable legends and images that celebrated the conquests of Roman soldiers. These coins were widely circulated throughout various cities in Armenia, reflecting the political situation of the occupied region.

The Roman coins of Marcus Antonius from 35 BC were the first to depict the full Armenian crown. These coins also featured the Latin transcription of “Armenia” and depicted the profiles of Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra. The coins of Marcus Antonius serve as the primary source for the political history of Armenia, as they reveal the occupation of Armenia and the fall of the Armenian kingdom. Coins struck during the reign of Augustus depicted the conquest of Armenia and showed allegorical representations of Armenia as a conquered bull or a young king begging for mercy for a captive Armenian soldier. These coins also featured the theme of the conquest in other ways, including a silver coin (didrachm) that depicted the coronation of the Armenian king Zenon-Artaxias by the Roman general Germanicus in the capital of Armenia in 18 AD.

Roman Empire. Trajan

98-117 AD

AE Sestertius

CNG eAuction 563 Lot 847

Roman coins minted between 115 and 117 AD commemorate Trajan’s campaign and the Roman conquest of Armenia. The depiction of Armenia as a woman lying beneath the Roman emperor’s feet exemplifies the Roman occupiers’ political subjugation.

Roman Empire. Antoninus Pius

138-161 AD

AE Sestertius

Ira & Larry Goldberg Auction 109 Lot 2152

Similarly, the Roman coins issued in 140 AD, featuring the coronation of King Sohemus Tigranes by Pius Antonius, offer insights into the attire of Armenian kings from the second century AD, as both figures are shown in full height.

In the middle of the second century, the relationship between Armenia and Rome is depicted through the visual elements of Roman gold, silver, and copper coins. These coins, which bear images of Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius, feature legends and symbols that signify Armenia. Marcus Aurelius’s coins represent the Roman conquest of Armenia and the submission of its kingdom. On the other hand, Lucius Verus’s coins represent the crowning of the Armenian king by the Emperor, who is seated on a high tribune. These coins were in circulation due to the flourishing international trade, which allowed the Roman Empire to spread information about Armenia to all its subjects. It is noteworthy that copper coins bearing Armenian symbols were not found outside of Rome and were not circulated in Armenia.

Sassanian Empire. Ardashir I

205-224 AD

AR Drachm

Leu Numismatik Web Auction 28 Lot 2075

The rise of the Sassanian dynasty and the decline of the Parthian kingdom had an impact on the circulation of money in Armenia, although this influence was not immediate. The introduction of Sassanian currency marked a new era in the monetary systems of Eastern countries. Ardashir Papak, the first king of the Sassanian dynasty, was still issuing coins during his reign from 205 to 224, and his successors continued this practice. However, the early Sassanian coins were not as widely recognized or respected as the Roman currency that was still prevalent in the global market at that time.

The discovery of a Sassanid coin in Armenia dating back to the rule of Ardashir Papak is notable. This silver coin was first unearthed in Garni in 1963 and is well-preserved, allowing for the examination of its unique typological features. Additionally, similar coins have been found in other areas of Armenia.

The Sassanids issued gold, silver, and copper coins. In Armenian sources, gold Sassanid coins were referred to as “դահեկան” (dahekan), which indicates a traditional connection to pre-Hellenistic nominals. Initially, gold Sassanid coins were issued in the weight norm of the Roman aureus, which was 8.19 grams. However, it should be noted that gold coins were not common in Armenia. In fact, such cases were relatively rare. Similarly, copper Sassanian coins were not commonly found. The most widespread Sassanian coin was the drachm, which was the primary monetary unit in Sassanian Persia. It was minted with approximately 4 grams of high-quality silver and was used in monetary transactions. During this period, Roman silver coins contained a significant amount of copper, which is why Sassanid drachms gradually became the leading form of currency. In addition to the standard silver drachm, the Sassanids also minted rare subgroups of 1/2 and 1/6 drachms, although these were not produced in large quantities and were not found in Armenia or neighboring countries.

Beginning around the end of the 3rd century, changes occurred in the circulation of money. An increasing number of Sassanid drachms were on the market, initially used alongside old Parthian and Roman coins. The prevalence of Sassanian coins in the region between the Araxes and Kura Rivers can be gauged by the hoards from the end of the 3rd and start of the 4th centuries found in the territory of Caucasian Albania. In this hoard, there are nearly 200 Sassanian drachms, along with rare examples of Parthian and Roman coins. This is not a coincidence but reflects the natural correlation that existed in the circulation of Transcaucasian cities at the end of the 3rd century. The Parthian and Roman coins in this hoard date back to the 1st-2nd centuries (Gotarzes, Vologases, Trajan, and Hadrian), while the Sassanian coins date back to the end of the 3rd century (Bahram II, 274-291). Despite a 150-year chronological gap between the new and old coins, they still circulated simultaneously. The close economic and political relations between Albania and Armenia during the Sassanid period led to the assumption that a similar correlation of Sassanid and other coins existed in Armenia, whose foreign trade during this period included international trade with Persia. It should be noted that only those Roman and Parthian coins that were valid for their silver quality for international trade were in circulation alongside the Sassanian coins. Merchants chose only the high-standard coins, which explains why the hoard from the 3rd century includes coins struck in the 2nd century that met the requirements of the market and were most corresponding to Sassanian standards.

In the latter half of the 4th century, Armenia began to mint coins in the style of the late Roman Empire, as evidenced by the silver coin hoard discovered in Yerevan. The presence of gold coins during this time was also evident. The gold-to-silver ratio was 1:14. Numerous examples of both late Roman and early Byzantine gold coins from the 5th-4th centuries have been found in various regions throughout Armenia.

The location of Armenia greatly influences international trade. In 408–409, a treaty was established between Persia and Byzantium, which made the primary city of Armenia, Artaxata, a key center for trade in the Near East. The archaeological excavations of Dvin reveal that the city was actively engaged in international trade during the 5th and 6th centuries. Byzantine gold coins were also present in Armenian marketplaces, indicating that caravans were used for trade. However, the lack of rich hoards of Byzantine coins from this time period suggests that their influence in Armenia was limited. Sassanian coins, on the other hand, were widely circulated in Armenia during the 5th century and played a significant role in both domestic and foreign trade in Eastern Armenia. The analysis of the coin hoards found in Armenia and neighboring regions of the Caucasus reveals two main groups of coins that were circulating in the Armenian markets during the 7th century: Persian and Byzantine. The Leninakan hoard provides evidence of the conflicts between these two groups in the territory of Armenia.

Sassanian Empire. Kawad I

488-531 AD

AR Drachm

Bucephalus Numismatic Auction 36 Lot 245

The earliest Sassanid drachms from this hoard date back to the reigns of Kawad I (488-497, 499-531), Khosrov Parviz (590-628), and Ardashir III (628-630). Meanwhile, the latest coins in the hoard are Byzantine hexagrams (16 pieces) issued by Heraclius (610-641) and his successors, as well as one Byzantine coin minted in 654-659. The typological data of the Byzantine issues suggests that they were struck in the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. On the other hand, the Sassanian coins were minted in various locations throughout Persia.

The findings from the excavations of Dvin, a prominent trading and craft hub, reveal that during the 7th century, Sassanian coins from Kawad I, Khusrow I Anushirawan, Horawzd IV, and Khusrow II Parviz were circulated in tandem with Byzantine coins from Emperor Heraclius (640-641). Specifically, the average weight of 169 Sassanian coins was between 3.85 and 4.05 grams, while the average weight of 98 Byzantine double military and hexagrams was between 6.50 and 6.90 grams each.

The drachms with images of the following Sassanid kings issued in Armenia during their reign are revealed by investigation:

- Yazdegard I 399-420

- Peroz 457/9-483

- Valkash 484-488

- Kavad I 488-497 and 499-531

- Khusru I 531-579

- Hormazd I 579-591

- Khusru II 591-628

- Ardeshir III 628-630

By their weight standards and images, they are not Armenian but purely Sassanian Persia state coins that differ from all the like only by the Pahlavi abbreviated legend for the name Armenia. Apart from Sassanid drachms minted in different provinces, which typically weighed around 4 grams of pure silver according to the ancient Attic weight standard (4.36 grams), there were occasional instances where silver coins were issued. Among these, a small number of silver pieces bearing the name of Yazdegard’s heir to the throne, Shapur, are worth noting. These coins were close in diameter and weight to a quarter drachm. Two examples of such issues struck with different dies have survived to the present day; one can be found at the State Hermitage in Leningrad, while the other is housed in the British Museum in London.

The coin kept at the Hermitage was not known to us until the second half of the 19th century when it was discovered in the collection of J. de Bartholomaei.

It is often speculated that larger quantities of these coins were struck despite the fact that only a few have survived.

The silver coins were not typical for the mass production of widely circulated drachms because they were small in diameter and lightweight. They were likely minted for special occasions, such as the enthronement of Shapur as king of Armenia. Movses of Khoren, who referred to the years 416-420, mentioned that Yazdegard, the Sassanid monarch of Persia, appointed his heir as king of Armenia.

During the 6th century, alongside Persian coins, local Sassanian industries enjoyed international circulation. At this time, an increasing number of gold and silver Byzantine pieces, including high-standard Byzantine solidus depicting images of Justinian I (527-565), Tibetus (578-582), Phocas (602-610), and hexagrams of Heraclius (610-641) and his sons, were found in Armenian markets. This is not surprising, given that in 588 Byzantine troops attacked Armenia, and though they did not capture Dvin, after the armistice, it shared a border with Byzantium. In 623, Byzantine troops succeeded in conquering Dvin, but five years later, a treaty between Persia and Byzantium returned the capital of Armenia to Sassanian rule. Finally, in 632, Armenia was occupied by the troops of Emperor Heraclius, whose coins were circulated in Armenian towns and could be found both in hoards and as individual examples. These Byzantine issues were minted in 615 and weighed twice as much as the former silver issue. Unlike the Sassanian, Byzantine Emperors made a concerted effort to establish their leadership in the global market for silver coins.

Byzantine. Leo V The Armenian

813-820 AD

AV Solidus

Heritage Auctions 3115 Lot 32334

Up until the end of the 7th century, Byzantine gold and silver issues featuring the images of Heraclius and his successors, as well as Sassanian issues, were utilized to meet the needs of Armenian markets. Despite the fall of the Sassanid Empire, in all provinces of the Arab Caliphate, including Armenia, its coins continued to be circulated, although the power itself was no longer in existence. Furthermore, while the type of Arab coins had not yet been established, many provinces of the Caliphate adopted Sassanian and Byzantine coin types. However, both Arab-Sassanian and Arab-Byzantine coins were not commonly found in Armenia and did not provide insight into the country’s monetary system. These coins are scarce throughout the Transcaucasia region. Consequently, the likelihood of them being used in Armenian towns was minimal. Sassanian coins were issued in central and eastern provinces of Persia, such as Jibal and Khurasan, while Byzantine issues circulated in trade centers in Palestine, Syria, and other areas that were once part of the Byzantine Empire. However, these coins rarely reached the southwestern regions of the Armenian Highland, and there is no evidence to suggest that they were permanently used in Armenia.

In the final years of the seventh century, Caliph Abd al-Malik implemented a special reform that established the primary tenets of the monetary system for the Caliphate.

Umayyad. Abd al-Malik

685-705 AD

AR Dirham

Stephen Album Rare Coins Auction 49 Lot 1852

The Umayyad gold coin weighing 4.25 grams, referred to as a dinar in Armenian sources, was not commonly found in Armenia or Transcaucasia. Instead, the silver coin weighing 2.97 grams, known as the dirham (Armenian dram), was the primary currency unit and was made of high-quality silver. Copper Umayyad coins did not have a fixed weight and varied between 1 and 9 grams but generally weighed between 3 and 5 grams. Unlike coins from the previous era, Arab examples did not feature human or animal images. Instead, they had inscriptions in Kufic script on both sides of the coin, mostly religious inscriptions from the Koran. The central part of both sides of the coin featured the most important inscriptions, while circular legends of religious characters and the place and date of coinage were also present.

In the 8th century, various mints of the Umayyad Caliphate struck different coins in Armenian towns due to trade relations. Additionally, the Umayyad Caliphate minted silver and copper coins in Armenian, Albanian, and Eastern Georgian towns, which were combined as one province called “Arminiya” by the administrative division of the Caliphate. The earliest Arab coin struck by the Umayyads in Armenia dates back to the 78th year of the Hijra era, corresponding to 697-698 AD. The mint activity continued for 50 years from A.H. 79 to A.H. 131 (698-699-148-149 AD). The existence of post-reform coinage signifies the complete domination of the caliphate over Armenia, Albania, and Eastern Georgia. However, these coins did not have a significant character and were not minted by any of the towns. Until the end of the 20th century, all coins of the 7th century had the same mint mark “Arminiya.”

The primary administrative center of Armenia was Dvin, where the majority of the coins bearing the mint-mark “Arminiya” were minted. Nevertheless, there were also coins struck with the “Dvin” (Dabil) mintmark. In the main city of Albania-Bardah, coins bore the name of the province of Arran as a mintmark.

The Umayyad copper coins known as fulus that were minted in Arminiya and circulated in the domestic market can be categorized into three main groups. Group A consists of fulus that lack both mint and date marks, bearing only religious characters. Group B includes fulus that have either date or mint marks along with religious inscriptions. Finally, Group C consists of fulus that bear not only the aforementioned information but also the names of the respective governors.

The abundance of Umayyad fulus discovered in Dvin bearing the “Arminiya” mint-mark and lacking in other locations suggests that these coins were exclusively minted in Dvin.

In the first half of the 8th century, in addition to dirhams and local coinage, coins from the Syrian, Iraqi, Khuzestan, and Fars mints were circulating in Armenia, reflecting strong trade ties with these regions. Contrary to the Sassanian and Byzantine issues, the silver Umayyad coins are relatively scarce.

During the second half of the 8th century, there was an increase in the circulation of money. This period coincided with the rule of the Abbasids, who took over from the Umayyads. It took some time for the transition to occur, and the first Abbasid caliph Saffakh did not mint any coins in Armenia during his reign from A.H. 132 to 136 (AD 750-754). Coinage activity began with the caliph Al-Mansur, who ruled from A.H. 136 to 158 (AD 754-775), and issued copper and silver pieces that adhered to the weight standards established by the Umayyads. The Abbasid coins featured religious inscriptions from the Koran, but unlike the Umayyads, they proclaimed the second half of the Islamic statement of faith, which is “Muhammad is the apostle of Allah.” The main monetary unit was the dirham, which weighed approximately 3 grams. The earliest Abbasid coin struck in Armenia was A.H. 143 (AD 760-761). Initially, the names of the governors were not included on the coins. However, by the late 60s of the 8th century, Abbasid dirhams and fulus bore the names of Caliphate successors and local governors.

The coins issued in Armenia and Albania from 759 to 833 feature more than 200 Abbasid governors in these regions. From the latter half of the 8th century onwards, Abbasid coins were minted in various locations throughout the province of Armenia. The specific mints that produced these coins are documented.

Abbasid Caliphate. Al-Mahdi

775-785 AD

AR Dirham

CNG Islamic Auction 5 Lot 303

From the second half of the 8th century, the Abbasids minted coins in various towns within the province of “Arminiya.” Abbasid coins with the following mint marks in Kufic script have been preserved: YAZIDIYA, BERDA’S, ARMENIYA, ARRAN, DERBAND, DABIL, HARUNABAD, HARUNIYYA, MA’ADAN-BAJUNAIS, MEDINAT ARRAN, TIFLIS, and BITLIS. The earliest of these issues was struck in YAZIDIYA and bears the date A.H. 140 (AD 757-758), while the latest was minted in ARMENIYA in A.H. 332 (AD 943-944), representing the province established by the final division of the Arab Caliphate. The central mints for Abbasid coins were located in Dvin (Dabil) in “Arminiya” and Bardaah in Arran, although other towns also issued coins.

As the Bagratid dynasty ascended to power in Armenia and neighboring regions, Abbasid coinage continued to be widely employed, playing a significant role in international trade from the 9th to the 10th century. Although it is unclear whether the kings of Armenia were involved in coinage activities, there is currently no evidence to suggest that they were during this period. Even the Armenian princes and the most powerful feudal kings of Shirak from the Bagratid dynasty, as indicated by the lack of coin hoards, did not mint their own coins.

From the end of the 9th century, particularly in the 10th century, in addition to Abbasid issues in Armenia, Kufic dirhams of independent and semi-independent Muslim emirs were also present. The Sadjids issued gold and silver coins in Armenia, with the main centers being Arran, Dvin, Bardaah, Maraghah, and Raily, where Sadjid dirhams and dinars were struck. In the second half of the 10th century, gold and silver coins of the Sallarids also appeared. However, both Sadjid and Sallarid issues were not numerous and were overshadowed by the mass of Abbasid coins. European hoards of Kufic coins indicate the penetration of Abbasid, Sadjid, and Sallarid issues into international trade. The spread of “Arminiya” dirhams into foreign markets was achieved indirectly through the global trade connections of the Eastern Caliphate. Silver Abbasid coins were widely accepted in international currency exchanges. The relationship between gold and silver during the 9th and 10th centuries was 1:10 or sometimes 1:14, which often changed depending on the value of the precious metals. Unlike gold and silver pieces, copper coins were meant for the home market. As before, the geographical situation of Armenia during this period provided certain advantages for the development of monetary-commodity relations. In the southwestern areas of the Armenian Highland, along with Abbasid issues, coins of the Hamdanids, Marwanids, and Uqaylids also circulated. However, these coins and the dirhams of the emirs of the Saffarids, Ziyarids, Bujids, Kakwayhids, and Samanids are rarely found in the northeastern regions of Armenia.

The use of Abbasid dirhams at mints in Syria, Iraq, and Persia was prevalent in the area between the Araxes and Kura Rivers.

During the 10th and 11th centuries, Byzantine coins, consisting of gold and copper, were prevalent in Armenia, while silver coins were less common due to the scarcity of the metal. Despite extensive research, no silver Byzantine coins from this time period have been discovered in Armenia or its surrounding regions.

During the 10th-11th century, the Byzantine Empire faced various issues. Specifically, coins were minted in Constantinople during this period. A large hoard of Byzantine coppers from the 11th century, depicting the image of Jesus Christ, was discovered in the ruins of Ani. This suggests that one of the Empire’s mints producing coins for the domestic market was located in Ani, the capital of the Bagratid dynasty when Byzantine troops occupied the area between 1045-1064.

Kingdom of Lori. Kiurike II Curopalatus

1048-1100 AD

AE Follis

Stack’s The Golden Horn Collection 2009 lot 3467

After the fall of the Ani kingdom, the Lori branch of the Bagratids, who were vassals of Byzantium, managed to retain their estates. They began minting their own coins bearing Armenian inscriptions, which was a rare occurrence. This act marked the beginning of national coinage in the territory of Armenia, although the national power had already ceased to exist. These coins, which were of the Byzantine type and were issued during the reign of Kiurik Curopalatus (1048–1100), featured the portrait of Jesus Christ on the obverse and were widely circulated in Transcaucasia during the 10th-11th centuries. The inscription on the coins read “God help Kiurik Curopalatus.” Regrettably, very few examples of these coins exist with date marks. Since they were made of copper, their circulation was limited to the domestic market, and they had no significant impact on Armenia’s monetary relations, which were characterized by poverty.

Toward the start of the 12th century, silver coins vanished from the economic scene in Armenian towns. At this time, copper coins minted by the Seljuqid dynasty gained popularity as a medium of exchange in the local market, whereas gold coins from the Byzantine Empire were commonly used for international trade.

From the 12th century to the start of the 13th century, copper coins from the Bagratid dynasty of Georgia were used in Armenia. These coins were of low value and were used in place of silver coins. The widespread presence of these coins from the 12th to 13th centuries indicates a close relationship between the cities of Eastern Transcaucasia in terms of poverty and money.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, in the southwestern areas of Armenia, copper coins of the Artuqid, Zangid, Danishmand, Mankujakid, and other dynasties in power after the fall of the Seljuks came into circulation. It should be noted that coppers from these mentioned dynasties from towns like Mardin, Hish Kayfa, Sivas, Malatya, Arzijan, and others penetrated into the northeastern regions of Armenia but were not in permanent circulation.

Kingdom of Georgia. Queen Tamar

1184-1213 AD

AE

Leu Numismatik Web Auction 24 Lot 4458

The end of the 12th century and the beginning of the 13th century are characterized by a wide range of circulation of Georgian coins. The majority of these coins are from the reign of Queen Tamar (1184-1213). The obverse of her coins bears the name of the queen and her second husband, David Soslan, in the mtavruli type Georgian letters. The reverse of the coins has a four-lined inscription detailing the titles of Queen Tamar, Queen George’s daughter, and Messiah worshippers. These coppers were issued with both date marks (1200 AD) and without. The latter type of Thamar coin (copper) is very rare in Armenia.

In the late 1220s, Georgian coppers of Queen Rusudan (1223-1247) circulated in the northeastern parts of Armenia. These coins were of the right form and had standard weights. Three Georgian letters on the obverse give the name of the queen and the date (447 years of Koronikon, 1227 AD). In contrast, the reverse side has a four-lined Arabic inscription representing the titles of the queen. During this period, in the 1220s, coinage of copper dirhams gave way to silver issues. Dirhams (dram) once again acquired their former significance as the main unit and had the same weight of 297 grams. Armenian markets used silver issues from the Seljuks of Asia Minor, and in later periods, Mongol dirhams from Persian and Transcaucasian towns.

Beginning in the 1230s, Armenian circulation was further developed by Mongol issues. Most early pieces date back to 1232-1233. These were the silver dirhams of Chinghizid Ögedey (1227-1241), issued without his name. Such anonymous silver pieces struck in Persia and Transcaucasia had Arabic inscriptions praising the justice of the Khan and also the abbreviated symbol of Islam. In addition, the Mongol issues of the 1230s and 1240s also represent the characteristics of Mongol weapons, such as bows.

Old names of monetary units were still valid during this period using Arab terminology. Thus, gold coins were called “dinar,” silver “dirham,” and copper “fals.” The Armenian names were: դահեկան (dahekan) for dinar, դրամ (dram) for dirham, and փող (pogh) for fals. Additionally, there existed heavier copper coins called դանգ (dang). Until the 1270s, Mongol dirhams circulated together with the dirhams of the Rum Seljuqs at Sivas, Konya, Kaisaria, and other mints. Later, the penetration of coins from Asia Minor decreased, and Mongol dirhams coined in Persia and Transcaucasia entered Armenian towns due to international trade. Hülaguid issues were struck in Iraq, Kurdistan, Kirman, Pars, Georgia, Shirvan, Asia Minor, and other regions of the vast Hülaguid territories.

Mongol Dynasty. Abaqa Khan

1265-1282 AD

AE Fals

Stephen Album Rare Coins Auction 37 Lot 2555

In certain regions with Armenian populations, during the reign of Abaqa Khan (1265-1281), coppers for the home market were issued with trilingual inscriptions in Mongol, Arabic, and Armenian. On one side of these coins, in the central field, there is the symbol of the Christian faith—the cross. Armenian and Arabic inscriptions, which are religious in nature, are placed near the cross; the Armenian reads “The Lord Jesus Christ,” while the Arabic inscription says “For the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost, the only begotten.” The Mongol inscription on the other side, without any sign, reads: “In the name of the Kagan coinage of Abaqa.” The presence of Christian religious formulae on the Hülaguid coins of the 13th century is of particular interest, especially since one of them is in Armenian. This suggests that these coins were meant for circulation among the Christian population, particularly the Armenians.

Unfortunately, the coins of Abaqa Khan have neither dates nor mint marks. However, the fact that the Armenian inscription appears on these coins indicates the demographic structure of the towns where they were issued and where Armenian was the main language. In many towns situated between the Araxes and Kura rivers, Armenian knights played an active role in economic life. The occurrence of Armenian legends on the Hülaguid coins reflects the peculiarities of the home market of Transcaucasian towns during the era of Mongol power.

Apart from coppers, the Khulaguid issues also included silver coins, but like the trilingual silver dirhams with Arabic and Mongol legends, they were not widespread in Armenian towns.

The Khulaguid coinage activities ceased at the end of the 13th century. At the beginning of the 14th century, by the reform of Ghazan Mahmud Khan (1295–1304), the Ilkhanate introduced a new monetary system with a main silver monetary unit of 2.1455 grams. Gold and silver coins were also developed, with the ratio of gold to silver being 1:12. Silver coins weighing 3 mitkals (12.78 grams) were called silver dinars, equaling six dirhams. One dirham weighed half of the half-Mithkal (2.13 grams). Double and single dirhams were also reported. A new unit, the tuman, equaling 10,000 silver dinars, came into existence.

Mongol Dynasty. Ilkhanids. Abu Sa’id

1316-1335 AD

AR 6 Dirhams

Leu Numismatik Web Auction 28 Lot 6245

After the reform, mints opened in different Hülaguid towns. This facilitated trade and craft in the centers of Armenia and neighboring countries, such as Ani, Garni, Arjiesh, Karin, Arzanjan (Erzinka), Sivas, Nakhijevan, and others, which struck post-reform silver coins. However, the reform of Hasan Khan could not prevent the collapse of the Hülaguid coinage. The scarcity of silver became noticeable. In the 1330s, dirhams contained an average of 1.43 grams of silver. By the mid-14th century, dirhams weighed half a gram. Such lightweight silver pieces came into circulation in Armenian towns from different regions of Ilkhanid power. The places where these coins were struck reflect the close economic relations between Armenia and the economic centers of Transcaucasia, Persia, Iraq, and Asia Minor. Shortly before the fall of the Khulagands during the reign of Suleiman Khan (1339-1344), in the craft and trade center of Armenia, Ani, copper bilingual (Arabic and Mongol) coins bearing the image of a human figure were issued, having only local significance. During the second half of the 14th century, appreciable changes in coinage activity in Armenia were not observed; light and debased dirhams of the last Ilkhanid were in circulation.

At the end of the 14th century, coins from new Muslim dynasties—Jalayirids, Timurids, Qara-Qoyunlu, Aq-Qoyunlu, and others of Mongol and Turkic descent—began to appear. No gold or copper coins were issued; the silver coins were quite light. For example, a Jalayirid silver dirham struck during the rule of Sheikh Umays (1356-1375) weighed nearly one gram.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the Timurids introduced a new monetary unit adopted from India called the “tank,” made of high-standard silver and weighing 6.20 grams, which equaled four Jalayirid dirhams. Gradually, these coins became even lighter. In Armenian markets, silver coins from various towns in the Near and Middle East circulated. Jalayirid coins from Tabriz, Ardabil, and Khui, Timurid coins from Baghdad, Samarkand, and other locations circulated alongside coins from Shamakhi, Urmiah, and other centers of Qara-Qoyunlu power. The mints of these dynasties also operated in historical Armenia, particularly in Garni, Bitlis, Nakhijevan, and Arzanjan.

This period also saw the expansion of economic relations between Armenia and Western European countries. Silver talers from European monarchies reached the northeastern regions of Armenia and neighboring areas. Caravans from India, Persia, Turkey, and Europe frequently passed through Armenian towns, facilitating this extended economic interaction.

Safavid Dynasty. Shah Ismail I

1501-1524 AD

AR 2 Shahi

Sincona Auction 88 Lot 1

A further stage of circulation development in Armenia began in the 16th century when the issue of Persian Shahs became widespread. Monometalism and silver issues of the Safavids played a leading role. During the reign of Ismail I (1501-1524), the main monetary unit was a silver coin weighing 9.37 grams, which was equivalent to 2 mithqals. Coins weighing 4, 2, 1, 1/2, and 1/4 grams were also struck. These early Safavid coins were called “new tanka.” In later periods, the weight of the tanka was reduced to 1 mithqal, equaling 100 dinars. Additionally, small silver coins known as “bisti” were struck, equaling 200 dinars.

At the end of the 16th century, it was necessary to change the existing monetary system. In 1595, by the reform of Safavid Shah Abbas I, a new silver coin called “abbasi” was introduced. This coin was made of high-standard silver and weighed 7.70 grams. Persian mints struck denominations of 2, 1, 1/2, and 1/4 abbasi, with the most widespread being the nominal of one abbasi. These coins featured the Shiite symbol of faith, the names of 12 imams, the name and title of the Shah, the mint name, and the date (in A.H.) in Farsi. Hoards showed that in Armenia, coins from the mints of Khhuvaiz, Isfahan, Tiflis, Ganja, and Tabriz circulated. In the first half of the 17th century, Safavid coins came into circulation alongside West-European large silver issues known as reichstalers, which weighed an average of 28 grams. One taler was equivalent to three abbases.

Ottoman Empire. Ahmed III

1702-1730

AR 10 Para

Münz Zentrum Rheinland Auction 194 Lot 2836

In the Erivan mint, silver Turkish coins were struck between 1703-1704. The most widespread were the so-called “onliks” and “beshlik” of the Transcaucasian coinage. Regarding gold issues, they were struck mainly for accounts and were insignificant. The Safavid gold coin was struck only on state occasions, particularly during the Shah’s enthronement. From the series of Erivan gold coins, only the “afshari” of Safavid Shah Tahmasp I (1524-1576) and gold “tumans” of Qajarid Fath-Ali Shah (1794-1834), struck between 1817-1820, are preserved. Together with these issues, European gold coins—Venetian ducats and later Dutch gold pieces—sometimes circulated in Armenia. To support domestic trade relations, copper coins were issued until the beginning of the 16th century and had state significance. Following 1511, towns under Persian power obtained an autonomous right to strike copper coins meant for domestic trade. In the second half of the 16th century, a new type of copper coin was established. These coins depicted animals, birds, fish, etc., on one side, with the nominal value, mint name, and date (in A.H.) on the other side. Out of a pound of copper, 64 pieces were struck (a pound of copper equaled one abbasi or 200 dinars). These coppers were struck each year, and at the end of the year, old coins were restruck; out of two old issues, one new piece was made. These coppers were meant only for the domestic market.

In later years, money circulation in Armenia underwent further development, with the mass distribution of gold, silver, and copper issues of the Russian Empire.

For references, see Mousheghian, Khatchatur. History of Armenian Numismatics / История нумизматики Армении / Հայոց պատմութեան դրամագիտականը. Anahit Publishers, 1997.